One of Scotland’s silent distilleries, Port Ellen’s whisky has become some of the most iconic in the world since its demise. As the popularity and demand for peated and smoky malts increases worldwide, Port Ellen’s diminishing stocks and growing rarity have made it a whisky only investors and serious collectors can afford to buy. Amongst the Islay malts, Port Ellen’s smoky character combines an oily maritime style with a lemon citric core. The Port Ellen style is also influenced by the refill casks traditionally used for maturation, which accentuate the smokiness while giving the malt a somewhat austere nature.

Port Ellen is set to reopen in 2021, the result of a booming single malt market and the cult status Port Ellen’s malt has attained since closure in 1983. This will be the second time in a century that Port Ellen has been resurrected, as it was also silent for 37 years between 1930-1967. Port Ellen’s revival is intended to build on the existing iconic reputation with the aim of producing new malt expressions and creating a new generation of whisky enthusiasts. Amid the expectations for Port Ellen’s reopening, traditional expressions and limited release bottlings will remain highly sought amongst whisky enthusiasts, collectors and investors.

Early years: Pioneer of the Whisky Industry

Located on Islay’s southern coast, Port Ellen was founded by Alexander Kerr Mackay in 1825. Originally a malt mill which supplied the illicit distilleries on the Oa peninsula, the new distillery derived its name from the nearby town – Port Ellen. Alexander Mackay went bankrupt within a few months, with control of Port Ellen passing to Mackay’s relatives John Morrison, Patrick Thomson and George MacLennan. In 1836, Port Ellen’s lease was taken over by the 21-year-old John Ramsay, a cousin of John Morrison.

Born into a Glasgow family of distillers and trained as an accounts clerk, Ramsay first arrived on Islay in 1833 to ascertain the management of family investments in the struggling Port Ellen distillery. Recognising Port Ellen’s potential Ramsay retrained as a distiller, then entered into a partnership with Walter Frederick Campbell the landowner laird of Islay to secure the Port Ellen lease in 1836. Under John Ramsay’s management Port Ellen would become a centre for innovation and the development of the whisky industry. At Port Ellen the first spirit safe was installed in the 1820s, although under Ramsay’s direction it was developed into the instrument which is now installed at every malt distillery in Scotland. Port Ellen would also be the site for the development of ‘patent stills’ used to produce grain whisky and the construction of the first duty-free warehouses.

A pioneer of the transatlantic whisky trade, John Ramsay would begin to export Port Ellen malt to the United States. Ramsay would also become established as a spirit importer of sherry and madeira, using the casks to mature the Port Ellen whisky. The whisky trade and development of Islay’s whisky industry would be aided by Ramsay and Campbell’s creation of a ferry service between the island and Glasgow, which also established Port Ellen as the island’s main ferry terminal. In 1869, the whisky blender and broker W.P. Lowrie became sales agent for Port Ellen, with the malt being sold for blending to clients including James Buchanan and John Dewar & Sons.

Declining fortunes

John Ramsay died in 1892, with his widow Lucy Ramsay inheriting and managing Port Ellen until her own death in 1906. Iain Ramsay succeeded his mother as owner and licensee in 1906, running Port Ellen until 1920. A combination of the Pattison whisky crash, the First World War years and economic depression forced Iain Ramsay to sell Port Ellen to the Port Ellen Distillery Co. Ltd in 1920, which was a partnership between blenders James Buchanan and John Dewar. In 1925, Buchanan and Dewar merged with Distillers Company Limited (DCL) transferring ownership of Port Ellen to DCL. Port Ellen was closed and mothballed by DCL in 1930, impacted by the effects of Prohibition and economic depression on the global whisky market.

Revival: Port Ellen’s Short-lived First Resurrection

Port Ellen would remain silent for the next 37 years, although DCL continued to use the maltings and warehouses at the site. In 1966, DCL began reviving Port Ellen initiating a modernisation and reconstruction programme to meet the rising demand for peated whisky, including installing two additional stills which doubled production to 1.7 million litres of alcohol when Port Ellen reopened in April 1967. A new drum malting facility was constructed alongside the Port Ellen distillery in 1973, supplying malted grain for DCL’s three Islay distilleries, Caol Ila, Lagavulin, and Port Ellen. Queen Elizabeth II would visit Port Ellen on the 9th August 1980, with the only official Port Ellen bottling released while the distillery was active produced to commemorate the royal visit.

The 1980’s whisky loch hit Islay hard, as blending companies needed only a small percentage of peated malt to produce bottlings of blended whisky. As DCL owned three Islay distilleries Port Ellen was deemed surplus to requirements and closed in May 1983, with the still house and bonded warehouses demolished. The Port Ellen stills were removed and allegedly shipped to India during the 1990s. In 1987, DCL declared that the Port Ellen distillery was closed permanently, with the surviving buildings repurposed for maltings. The Port Ellen maltings would survive due to the 1987 Concordat of Islay Distillers, an agreement between the active distilleries on Islay and Jura to all acquire a percentage of their malted barley from Port Ellen to protect jobs. Port Ellen’s revival era lasted for only 16 years, and Port Ellen seemed destined to join Scotland’s lost distilleries when the distilling licence was cancelled in 1992.

Port Ellen: A Ghost Distillery

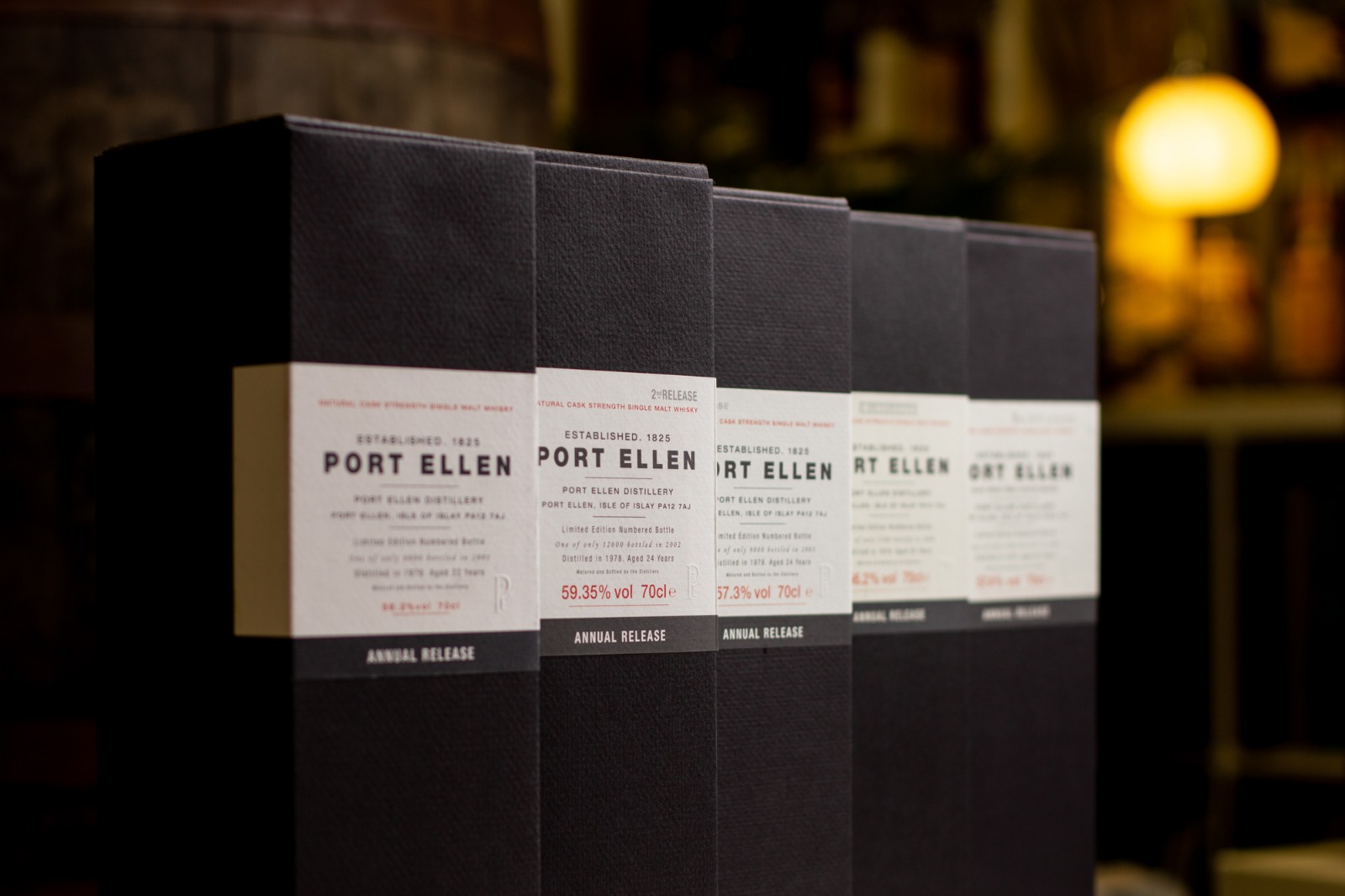

Although the drum maltings survived Port Ellen would become one of Scotland’s ‘ghost’ distilleries, those which have disappeared from productive life but whose whiskies still exist in the remaining stock and bottlings. Originally only intended as a blending malt and often filled into inert refill casks, Port Ellen has become the rarest of the Islay malts and considered iconic and highly sought across the world. Port Ellen first appeared as a single malt when released twice as part of the Rare Malts Selection of whiskies bottled from silent distilleries, first as a 20-year-old expression in 1998 and followed by a 22-year-old bottling in 2000. In 2001, a cask strength Port Ellen bottling was amongst the first single malts released as part of Diageo’s annual Special Releases, with a Port Ellen expression subsequently appearing each year until 2017.

The popularity of the Port Ellen Special Releases prompted a number of independent bottlings produced from the surplus whisky loch stock sold off when Port Ellen was demolished, which have further enhanced Port Ellen’s reputation as a collectable cult whisky. A 39-Year-Old Port Ellen bottling in 2019 would be the first release in Diageo’s new Untold Stories range, commemorating the early innovation at Port Ellen which shaped the development of the whisky industry.

Looking To The Future: Port Ellen’s Second Resurrection

On the 9th October 2017, Diageo announced plans to reopen the Port Ellen and Brora distilleries, both previously closed in 1983, as part of a £35 million investment. For Port Ellen the proposals included restoring the original kiln building and seafront warehouses alongside the construction of a new still house and visitors centre, creating a Port Ellen ‘brand home’. The revived Port Ellen will produce a medium-peated malt, and will have a production capacity of 800,000 litres of alcohol a year. Port Ellen will be equipped with four stills, with two replicating Port Ellen’s original copper pot stills fabricated using old equipment designs. A second pair of smaller stills will be used to create new experimental whiskies.

Diageo aims for Port Ellen to reopen and resume production in 2023, suggesting the first release could be a 12-Year-Old expression depending on the casks used for maturation – meaning it could be the early 2030s before any ‘new’ Port Ellen reaches the market. The wait could be longer if Diageo succeeds in recreating Port Ellen’s past austere smoky malt style, a character which developed after prolonged maturation in refill casks. Until then it is likely the last remaining old stock will be carefully released as limited collectable bottlings used to promote Port Ellen’s reopening and keep the brand name alive, as Port Ellen begins a new chapter in its distilling history.