There are many different ways of investing your money in assets or stocks, and some carry more risk than others. One of the most risky tactics in investment is the ‘Greater Fool Theory’.

The Greater Fool Theory can also be found in whisky investment. But what exactly does it mean?

The Greater Fool Theory is often used within the context of stocks and shares where the inherent value of the asset can be calculated by its ability to generate cash flow and improve the health of the business. However, the theory can be seen in a variety of investments, including the housing market and luxury items such as watches, and of course… whisky.

To many, the world of investment and the concept of the Greater Fool Theory can seem complex and overwhelming, but there are just a few key ideas to understand to help you avoid investment pitfalls.

Market Bubbles

The Greater Fool Theory arises in conjunction with the idea of market bubbles. A market bubble is an economic phenomenon where the prices of specific assets rise excessively beyond their fundamental, inherent value. Whilst it is not confirmed exactly what causes a market bubble, there are two components that are required to increase the likelihood:

- An expansion of credit so that people can spend excess capital

- A narrative that people are excited to pay money for

Once the conditions are set, there is an outburst of irrationality where people believe that assets are worth something because other people are buying them, creating an increase in demand, which in turn pushes up the value. It is a self perpetuating cycle of expansion where assets become so overpriced because people are buying the asset for the sake of owning it rather than the value of the item itself.

Most famously, the housing bubble of the early 2000s saw house prices increase exponentially, to the point where most were massively over paying for their homes. Another example is the dot-com bubble where massive speculative investment was made in internet and tech companies in the late 1990s.

Eventually, the bubble will pop. It is this eventuality that makes the Greater Fool Theory so risky. So how do market bubbles relate to this theory?

Greater Fool Theory As An Investment Tactic

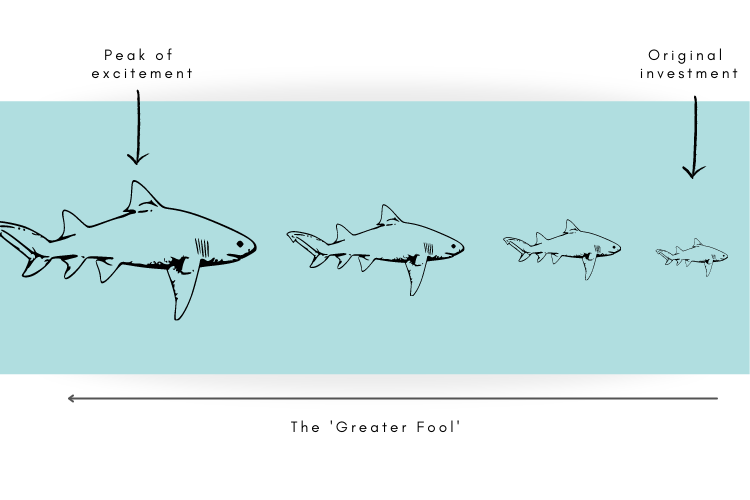

Investors who prescribe to the Greater Fool Theory believe that money can be made by buying overvalued assets and selling them on for profit, as there will always be someone willing to pay more than they did i.e. there will always be a greater fool.

When buying assets for an inflated price, investors are in no way concerned with the inherent value because they aren’t holding the assets in the long term – their concern is, therefore, purely the ability to sell the asset on.

The excitement and fanfare surrounding market bubbles create buyers that are willing to spend a bigger percentage of their excess capital to secure the relevant asset. Those buyers become the greater fool to the seller as they are willing to be led even further from the original inherent value of the asset.

However, using this theory is incredibly risky because at some point the bubble will pop. No one can foresee at what point this will occur, but eventually buyers will begin to realise that they are overpaying. For example, with the housing bubble, buyers began to realise that the homes they were rushing to buy weren’t worth their inflated price.

As an investor engaging with the Greater Fool tactic, the aim is to not be the last one holding the asset when the bubble pops. At that point, the value of the asset rapidly decreases and shrinks back to its pre-bubble value. This can make the asset difficult to sell as buyers become aware of their buying power.

The large risk associated with betting on market bubbles inevitably increases the chance of failure. As such, the Greater Fool Theory is not recommended as a long term strategy and investors would be wise to focus their efforts on more steady and reliable investments.

The Greater Fool Theory and Whisky

Something that we go into great detail about in our investment guide is the difference between vintage collectible bottles and the modern releases, and this is relevant to the Greater Fool Theory too.

Distilleries that can create that narrative and excitement around their newest release can create a localised market bubble for their product. This results in bottles that exceed their estimated secondary market price by huge amounts due to the belief that the bottles can be ‘flipped’ and resold to another buyer for much more.

There is an argument that when it comes to whisky, the Greater Fool Theory doesn’t apply and that the rapid increase in value for new releases is a speculative investment. This would mean that buyers can somewhat predict the growth of an asset based on previous performance. In the case of Macallan, for instance, as the world record holder for most expensive whisky ever sold at auction and a plethora of other incredibly high value luxury releases, buyers feel confident that new Macallan releases will perform well. This confidence creates a demand for new bottles whilst they’re still reasonably priced, with the assumption that their value will grow quickly upon release. This is often coupled with the belief that as whisky doesn’t produce cash flow like stocks or bonds, that it doesn’t have an inherent value, further perpetuating the idea that bottles that exceed their expected value are the product of speculative investment in the industry.

However, assuming that speculative investment is the cause of price hikes for whisky ignores the fact that it is generally accepted the whisky industry hit its peak in 2018. The whisky industry has spent the last twenty years or so repositioning whisky as a luxury asset, and has reached the peak of its curve. The wider public are aware of the lucrative nature of whisky and have seen its growth as an industry.

Greater Fool Theory Case Study: Macallan Archival Series

The Macallan Archival series is the perfect example to demonstrate the Whisky Greater Fool Theory. The Archival series, currently comprising of Folio 1 to 6, is a no-age-statement series that began in 2015. The Folio 1 bottle entered the secondary market at £280 in 2015 and whilst it did increase in value steadily over the next two years it never sold for more than £750. However, in 2018 Macallan opened a brand new state of the art distillery facility and visitors centre. In 2018, the value of the Folio 1 on the secondary market shot up to an average of £1500. Whilst a causative relationship cannot be conclusively drawn between the new distillery and the price of the Folio 1, it is likely that the excitement and narrative Macallan crafted around the opening would have contributed to creating a market bubble.

Once the first release began to rise in price, the subsequent releases followed suit and thus began the self perpetuating cycle of investors. As whisky investors saw the price increase for the Archival Series, more bottles were bought on the secondary market creating a demand, increasing the price further. This cycle continued and the Folio 1 peaked at £10,000 in April 2021. For a no-age-statement, somewhat generic release of Macallan this is far beyond what was expected of this bottle’s performance.

With the later Folio releases, 5 and 6 particularly, the bubble appears to have popped. On the secondary market the Folio 6 is currently achieving around the £900 mark, which is much more in keeping with what we’d expect. Oddly however, the Folio 1, and to some extent 2 and 3, has maintained its bubble price. Perhaps with the Folio 1 it is due to the status that comes with being the first edition in a series, but investors are often paying £8000 for this bottle.

So why are the Folio bottles part of the Greater Fool Theory? It comes down to whether the prices are fair, for instance, £10,000 for the Folio 1. When compared to other Macallan bottles, this price doesn’t seem reasonable. For example, the 1957 25 Year Old Anniversary Malt, bottled in 1983, is a Macallan bottling with a vintage, from a highly collectible series, and with a strong history. The 1957 25 Year Old also scored 93 points on WhiskyFun, giving it a place on the ‘winners’ list ensuring that this is a bottle for both collectors and drinkers. Further to this, whilst there are over seven hundred Folio 1 sales at auction since its release in 2015, there are just 69 1957 Anniversary Malt sales, making the Anniversary Malt considerably scarcer than the Folio. So why then can you buy the Anniversary Malt for an average of £4500 but the Folio 1 will cost you £8000?

This phenomenon can only be explained by the Greater Fool Theory. By all the criteria of a collectible whisky bottle, the 1957 25 Year Old Anniversary Malt is a better investment and yet on the secondary market it is half the price of the Folio 1. The new distillery opening in June 2018 created the market buzz around Macallan and increased the value of new releases beyond their expected value. Collectors became so determined to get the latest releases from Macallan that they were wildly overpaying. The Folio bottles are not the only Macallan releases to experience this; the Macallan Genesis released in 2018 experienced a mass hysteria with gridlocked roads near the distillery upon its release. With the new distillery now in the distant memory of collectors and investors, the bubble has somewhat popped and prices have begun to return to normal and the greater fools of Macallan have perhaps come to their senses.

Macallan have stated that there will be 24 releases in the Archival series and so it will be interesting to see if the Greater Fool Theory arises again or if the bubble remains popped.