We all know and love peated whisky, but with climate change on the rise and growing concerns about the sustainability of peat, is the profile of whisky about to change forever?

Contents:

- What Is Peat and How Is It Made?

- What Is Meant By Peat Flavour in Whisky?

- Where Does Whisky Get Its Peat From?

- What Role Does Peat Have in the Environment?

- Is Peat Sustainable?

- Are There Any Peat Alternatives?

- So where does that leave whisky and peat?

What Is Peat and How Is It Made?

In order to understand the growing concerns about peat, it helps to understand exactly what it is and how it is made. Peatlands are a wetland ecosystem where waterlogged and acidic conditions prevent plant material from fully decomposing. At its most basic, peat is simply a layer of partially decomposed organic matter.

Peat is made up of bog plants such as sphagnum moss, sedges, and shrubs. Where ordinarily, those plants would decompose and release carbon dioxide, the waterlogged conditions of peat bogs create an oxygen free and highly acidic environment where decomposition slowed. Partially decomposed organic matter builds up and compresses over thousands of years, creating what we know as peat.

Because of the high organic matter content and ease of farming, dried peat makes an excellent fuel source and fertiliser. In remote and generally treeless peatlands peat farming for fuel is widespread and it has been historically used by many distilleries in the whisky industry to dry the malted barley. This in turn imparts distinctive ‘peated flavours’ to the whisky.

What Is Meant By Peat Flavour in Whisky?

The team ‘peated flavour’ in whisky has become a bit muddled, and it is rarely used in the same way twice. As our sense of smell is responsible for approximately 80% of what we taste, it is the aromatic compounds in peat that are so important for that peated flavour. Now, the science behind peat in whisky can get quite complicated, but we’ve done our best to lay it out as simply as we can.

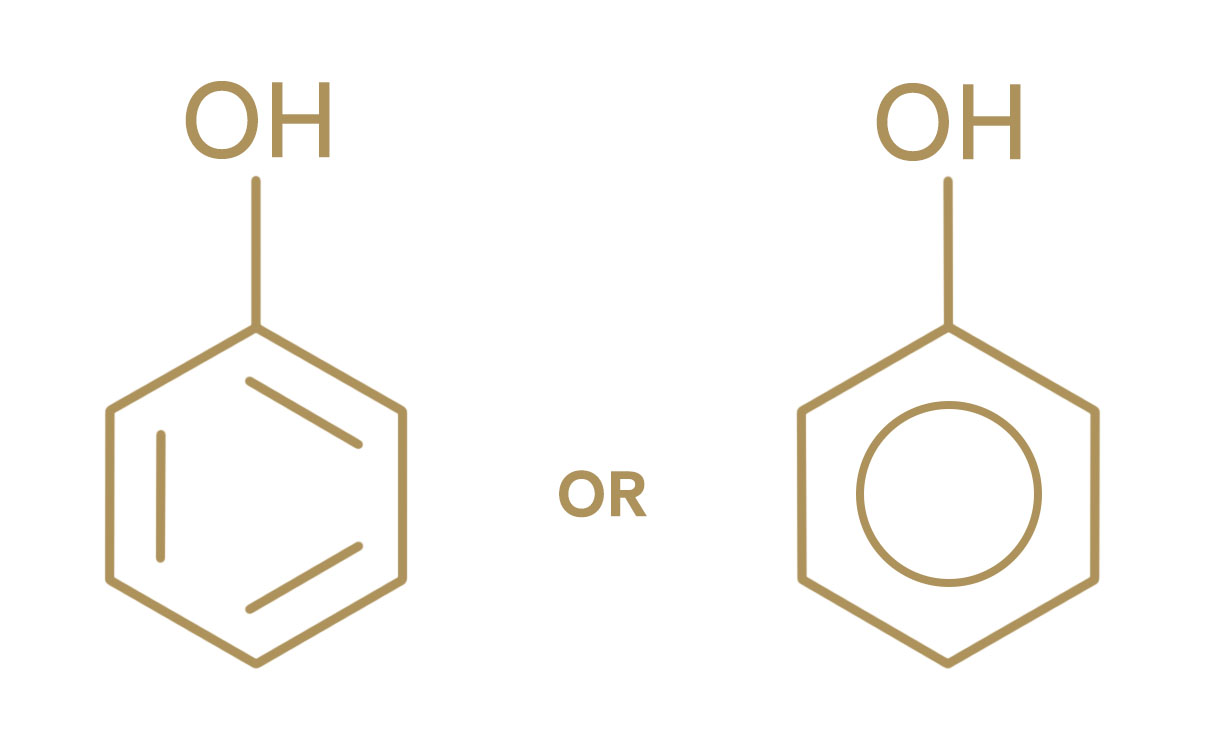

The first thing to understand is the difference between ‘phenols’, plural, and ‘phenol’, singular.

Phenol, in the singular, is the most basic variation of these chemical compounds. Its molecular structure is also known as carbolic acid or benzenol. Combinations of the phenol molecules create the more complex phenols.

Phenols are a classification group of chemical compounds, comprising many different molecular variations of aromatic and hydroxy structures. There are more than eight thousand phenolic compounds deriving from plants alone. Phenols have many different uses and are often synthesised for industrial use.

A good analogy for this would be looking at diamonds and coal. Both of these are made from carbon molecules which are arranged in different ways to produce two very different results.

When peat is used as a fuel source in whisky production we now understand that Phenols create a film on the surface of the malt, imparting their flavour during the kilning process. The strength of the peated flavour then decreases throughout the whisky making process.

For a long time we were unable to pinpoint exactly what makes the peaty flavour in peated whisky, and phenol became a generic umbrella term that is often misunderstood. However in 2019 a study by Jelen, Majcher, and Szwengiel was released that set out to identify the key odorants of peated whisky via volatile compounds, i.e. phenols.

In their study, they set out to assign each aromatic compound a flavour dilution score. That is, when diluting the whisky by 4 each time, how many times can it be diluted and still be identified as a peated whisky sample. And from that, through gas chromatography olfactory, which compounds were responsible for the ability to distinguish peated whisky from unpeated single malt, blended whisky, and American whisky.

Twenty compounds were identified with flavour dilution values and 8 of these were volatile phenols. The two phenols most responsible for the medicinal, peaty flavour of peated whisky are guaiacol, or 2-methoxy phenol, and 4-ethylguaiacol. Both have a flavour dilution score of 2048, meaning that after 5 rounds of dilution, these two compounds could still be identified and used to distinguish peated whisky. In comparison, phenol, the most basic molecule of the phenolic group, only has a flavour dilution score of 32, meaning that after two rounds of dilution, this compound was unidentifiable.

Guaiacol and 4-ethylguaiacol are found in lignin. Lignin is a complex organic polymer responsible for the structure of plant tissues and is found readily in peat. But just as importantly it is not unique to peat, which we will go into in more detail below.

Key takeaways:

- Phenols are complex molecules imparted to whisky when peat is used to dry the malt.

- Two main compounds are responsible for the peat flavour in whisky: Guaiacol and 4-ethylguaiacol

- The compounds are not unique to peat and could be extracted from other sources.

Where Does Whisky Get Its Peat From?

The whisky industry draws its peat from two main sources. The first is Northern Peat and Moss, managed by Neil Godsman, a company operating out of Aberdeenshire that supplies approximately two thirds of the peat used in Scotland. In an article with The Times, Godsman explains that he manages over 700 acres of peatland but he cannot harvest from 300 acres because it is protected via SSSI status, or ‘site of special scientific interest’. He goes on to explain that their 300 acre peat bog at St Fergus will be fully excavated within the next decade, leaving the company without any sites that can be mined.

So, within the next decade, the amount of peat available to the whisky industry will plummet by two thirds.

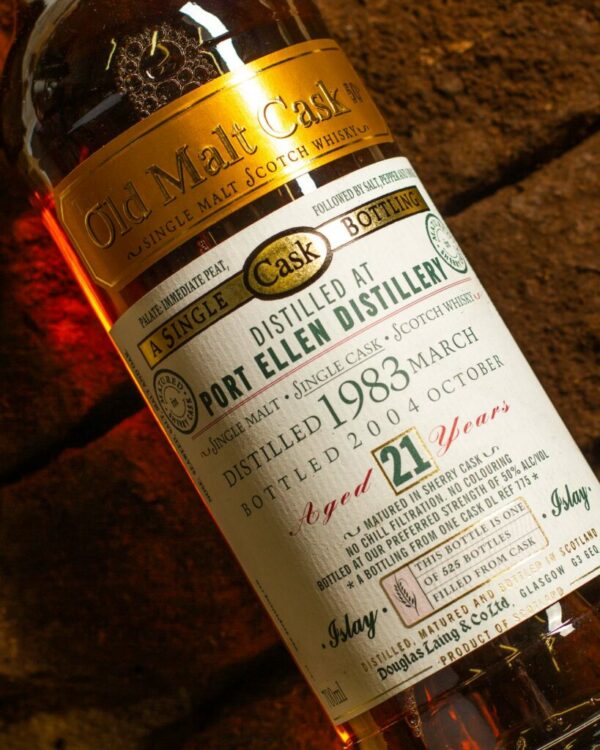

The remaining third of peat available to the whisky industry “belongs” to the drinks giant Diageo. At their Port Ellen Maltings Diageo currently have extraction rights for a 1000 acre site at Castlehill, which is currently owned by NatureScot, the Scottish Nature Agency. But as we will go into in a minute this is a rather contentious set up and may be subject to change.

Key takeaways

- Peatlands are becoming increasingly protected under SSSI status

- One of the two main sources of peat for whisky is set to run out in the next decade

- NatureScot are under increasing pressure to revoke Diageo peat contract

What Role Does Peat Have in the Environment?

Peatlands are an incredibly valuable and underappreciated ecosystem. It supports a huge ecosystem, provides a quarter of the UKs drinking water, helps prevent flooding, is invaluable to rural tourism and if all that wasn’t enough; the amount of carbon stored in Scottish peat alone is the equivalent to 140 years of Scottish carbon emissions.

UK peatland stores the same amount of carbon as the forests of the UK, France, and Germany combined and stores the equivalent of 20 years of all UK CO2 emissions.

However, when peat is used for whisky production or gardening and agriculture, peat bogs must be ‘mined’, where the peat is cut into blocks. When this mining is done, major changes occur in the bog:

First: The bog is drained. As soon as this occurs, the plant matter in the bog begins to decompose, which releases greenhouse gases, such as carbon dioxide, into the atmosphere adding to climate change.

Second: Once the peat is drained many of the key benefits of the bog are lost, from flood prevention to recreation and biodiversity.

Third: The remaining carbon store of the peat is released when the peat is burnt.

The combined consequences of peat mining therefore are incredibly detrimental to the environment and emit an average of 400,000 tonnes of carbon every year.

However, peat is incredibly popular, and not just in the whisky industry, because it is incredibly cheap and easy. This fact makes it very difficult for sustainable alternatives to compete.

Key takeaways

- Mining and burning peat has a significant carbon footprint

Is Peat Sustainable?

The short answer? No.

Some advocates for peat use have argued that peat is a renewable source of energy as it comes from naturally occurring matter, however this is most definitely not the case. The definition of renewable is that the fuel source can regenerate on a human time scale but it takes around 1,000 years to regenerate one metre of peat.

For added context, there are 3 million hectares of peatland in the UK, which have been accumulating since the last ice age: that’s twelve thousand years worth, which we think is a little outside the realm of a human time scale!

So why is peat still in use then? The simple answer is that peat is cheap, however the real answer may be slightly more complex. Income from peat mining has decreased from a peak of £119 million in 1997 to £36.2 million in 2015. The whisky industry on the other hand, contributes five billion pounds a year to the UK economy. Peated Scotch whisky enjoys global renown; Johnnie Walker is the fifth most popular whisky in the world and has a distinctive peated character as part of its world famous series.

As previously discussed, the phenols that contribute the distinctive peated flavour of whisky have been isolated, and can be synthesised. However, working out how to generate them in whisky requires expense, whereas peat is cheap, readily available and easy to argue for because of its historic use, and possible economic contribution.

Various government policies have been released over the last decade, starting in 2010 with the first DEFRA paper and then another released in 2022. They aim to invest £50m in peatland restoration by 2025 in England, and £250m over the next ten years in Scotland. This involves re-wetting peatland and ground protection projects.

With these policies all posed against peat mining, if left as it is the whisky industry may go from using 1% of all mined peat, to the sole user of peat. That means the drinks industry would be responsible for releasing the equivalent of 140 years worth of carbon emissions to flavour an alcoholic drink…

Furthermore a representative of NatureScot, Ben Ross, claims that extraction rights to Castlehill were granted to Diageo as a “sacrifice” in order to protect other, more important, peat bogs. Ross also acknowledged that it was an opportunity to work with Diageo and the whisky industry to restore peat bogs where possible, but he does pose the question as to whether there are other solutions to produce the same whiskies.

As it is such a cheap fuel, the whisky industry has not had an incentive to find an alternative, however if peat quantities continue to deplete, brands not owned by Diageo such as Ardbeg, Laphroaig, and others will have no choice but to find an alternative source of their signature flavour profile given the short time frame for depletion at their existing peat source.

Key takeaways

- Peat is not a renewable source of energy by current definitions

- Government policies aim to restore and protect peatland

- Rising pressures and government action will dramatically reduce the peat available

Are There Any Peat Alternatives?

So, if we can’t continue to use peat and we can’t imagine Laphroaig or Ardbeg without peat, then an alternative must be found.

Now, let’s be clear here: the whisky industry is stuck in its ways, but this is by no means the first time that external changes have forced this multi-billion dollar industry to find suitable alternatives to something that was once perceived as crucial to certain types of whisky: I’m talking about sherry casks of course. The industry had to work out how to replicate the impact of storing whisky in sherry casks when transport sherry casks stopped being readily available (see our video on sherry casks) and yet, we still have sherried whisky today! My point being, the industry just needs an incentive before it will look for a solution.

A sustainable peat alternative produced from organic matter known as Biochar is already available. As mentioned earlier, the two key phenols that create the ‘peated flavour’ of whisky are both found in lignin; which is in the cellular structure of all vascular plants. It seems likely that a version of biochar could therefore be adapted to create a suitable alternative to peat in whisky.

Biochar vs Peat

So what is biochar? Biochar is a high carbon form of charcoal that is produced via pyrolysis – the heating of organic matter at extremely high temperatures in the absence of oxygen. It is essentially commercially made peat using the same materials as peat but using technology to speed up the production.

Furthermore, phenols can be recovered from charcoal, which would suggest that they can also be recovered from biochar.

Biochar is preferable to peat in several key ways:

- The process of creating Biochar stabilises carbon in the final material, which reduces direct carbon emissions.

- It can be produced sustainably using either sustainably grown organic material or left-over material from other processes – such as the leftover draft from the whisky making process.

- Any greenhouse gases produced in the production of Biochar can be captured during the creation process.

- The heat necessary to create Biochar can also be used as a byproduct to produce energy.

- Bio-oil can be collected as a byproduct of the production process.

There are many advantages to Biochar and it seems likely that it is only a matter of time until Biochar (or something similar) is adapted as a peat replacement in whisky. Perhaps if Diageo or Pernod Ricard purchase the company?

Key takeaways

- A peat alternative must be found if peated whisky brands such as Laphroaig or Ardbeg are to continue without using environmentally damaging peat as their source of phenols

- Biochar is the leading alternative to peat at the moment

- It is likely that the phenols responsible for the peaty flavour of whisky can be found in biochar as they can be found in charcoal.

So where does that leave whisky and peat?

There is a general acknowledgment by the whisky industry and by environmentalist bodies alike that both the environmental impact of peat bogs and the cultural significance of peated whisky in Scotland are important and should be considered.

However, the extremely long term regeneration period of peatland leaves many wondering if the environmental cost is worth the reward. The Committee on Climate Change assessed that for every £1 spent on peatland restoration, there is £4 worth of social benefit through reduced emissions, improved water quality, and flood mitigation, which at a time of expedited climate change is an incredibly strong argument for banning the use of peat altogether.

On the other hand, the whisky industry has an incentive to negate these arguments. Of the total peat used yearly, peated whisky production accounts for just 1%, with the majority being used for farming. However over time the proportion used by farming is likely to drop due to government incentives, which means the percentage used by the whisky industry is going to rise.

The actions and goals set out thus far by various environmental bodies, such as DEFRA and NatureScot, have focused on the agricultural farming and gardening aspects of the peat issue, reflecting the make-up of consumers. A spokesperson from Diageo expressed in an article with The Times that “given that a large proportion of Islay’s population is involved in whisky production, adding to the £5 billion or so in value whisky brings to the economy annually, it seems foolhardy, to say the least, to limit the island’s peat extraction.”

There seems to be a subtle dichotomy emerging. Whilst government and environmentalist bodies are looking to phase out the use of peat altogether, the Scotch Whisky Association (SWA) and drinks companies such as Diageo are focusing on sustainable yet continued use of peat. But can peat use ever really be considered sustainable considering what we have talked about already?

Whilst it is no surprise that these opinions have formed, it is difficult to predict where this will end. The obvious divide here is always going to be economic contribution. As Diageo states, whisky contributes billions of pounds to the economy every year and employs whole communities in rural areas of Scotland and it is likely this has kept the focus away from the impacts of peat use for the last decade.

However, with mounting pressures on world leaders to take accountability for their nation’s carbon footprint, economic contributions may no longer be enough. Regardless of economic impact, peatland is limited and running out, and without a change in status quo or significant research into alternatives, peated whisky will likely become much rarer over the next decade.

It seems best for all involved that rather than digging in their heels and risking the future of peated whisky in Scotland, an alternative should be sought.