The laws surrounding Scotch Whisky are there to protect Scotland’s national drink, ensuring that the quality and production of whisky remains the same, preserving a beverage that has been enjoyed for many generations.

However, it may surprise you to know that, at times, the laws surrounding Scotch Whisky were far more political than they were about the preservation of whisky.

In this article, we will be delving into the politics of prohibition, our former teetotalling Prime Minister, and what this meant for the industry as well as the lasting effects that it still has today.

The Early Days of Scotch Whisky

Perhaps it should come as no surprise that many of the Scotch whisky laws stem from political issues, considering that Scotch whisky distilling was, for a long time, a bit of a headache for the government.

The first record of Scotch whisky distilling dates back to 1494. Tax records from this year show an entry that reads “Eight bolls of malt to Friar John Cor wherewith to make aqua vitae.” ‘Aqua vitae’ (Latin for ‘water of life’) is the name by which Scotch whisky was commonly known in its early forms.

The popularity of this strong, alcoholic beverage began to soar, and in 1644 the Scottish Parliament decided that it was their turn to profit from the growing industry. They placed taxes on Scotch whisky at a rate of two shillings and eight pence per half gallon.

By this time, Scotch whisky has been distilled for 150 years without taxation. Distillers did not take very well to the new taxes on their industry, and so illicit distilling became very prominent. It is estimated that, near the end of the 18th century, taxes were so high that only eight distilleries in Scotland were paying their taxes. Bear in mind, also, that much distilling was done at home and not at a licensed distillery.

The Excise Act of 1823

For many years, distillers continued to distil and smuggle whisky illegally, going to extreme lengths to hide from the excisemen, whose jobs it was to enforce the duty laws.

It was the Duke of Gordon who finally prompted change after he grew tired of the illicit distilling, much of which was taking place on his (extensive) property. He proposed that the government should make whisky distilling profitable for distillers in order to reduce illicit distilling and smuggling.

And so, the Excise Act of 1823 was passed, legalising the distilling of whisky in exchange for a £10 licence fee and set taxation per gallon of alcohol.

In response, smuggling began to die out, and left standing some of the great distilleries that we know and love today, such as Strathisla, Glenturret, Bowmore, and Littlemill.

Throughout the 19th century, the popularity of Scotch whisky (malt and grain, which came into being in the 1830s) continued to grow, with the love of the spirit reaching places such as South Africa, Japan, Vietnam, Canada, and more…

This rapid expansion was helped along by a small insect known as the phylloxera beetle. In the 1880s, these small beetles completely devastated vineyards in France that were relied upon to produce beverages such as wine and brandy. Scotch whisky replaced wine and brandy in the hearts of many.

The 1900s, The Teetotal Prime Minister, & War Time

Now, the 1900s is where it gets interesting, but also quite complicated…so stay with me.

The early 1900s saw the popularity of whisky continue to grow, and it was decided that an official body needed to be set up in order to protect the industry. As such, in 1912 the Wine & Spirit Brand Association was founded. This has now evolved into the Scotch Whisky Association.

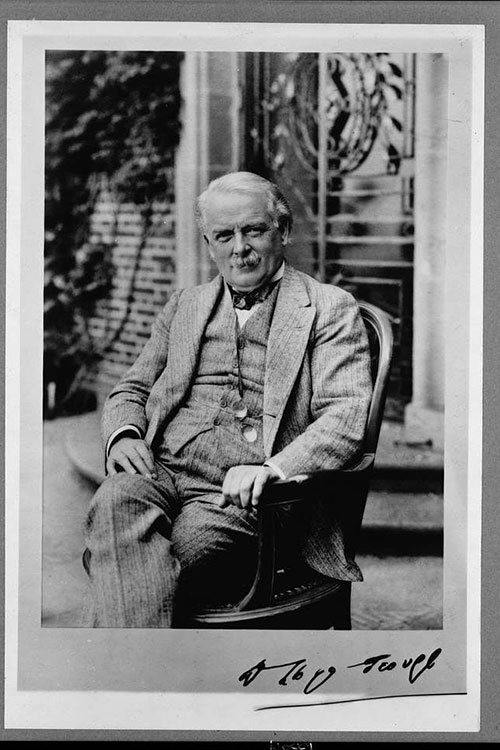

The prospering industry, however, was affected heavily by the onset of the First World War in 1914. There was pressure on the industry to contribute to the war effort in any way it could. And so, Chancellor of the Exchequer David Lloyd George founded the Central Control Board, which held jurisdiction over alcohol sales on military bases and large centres of population – so, most places. The board was also intent on implementing legislation to lower alcohol consumption in the population. David Lloyd George was not a drinker, and in his mind the consumption of alcohol was harming the war effort.

In 1915, Lloyd George’s budget included a proposal to double the duty on spirits. As you can imagine, the industry was not happy about this and countered that if Lloyd George dropped his proposals, distillers would agree not to release Scotch whisky from the cask until at least three years had elapsed. This meant that less alcohol would be available for consumption in the short term, something that Lloyd George was pleased by. Hence, the lasting law that Scotch whisky must be matured for at least three years in the cask.

In the same year, the Control Board allowed whisky to be sold at 35 degrees under proof, which was then the standard measurement for alcoholic strength. In ABV terms, this is 37.2% ABV. This was a significant drop from the previous legislation, which allowed whisky to be bottled at between 44.6% and 48.6%.

1916 saw Lloyd George gain even more control over alcohol production, when the government gave the Board permission to ban distilleries from producing if they did not have a licence from the Ministry of Munitions. No prizes for guessing who this sector was run by at the time.

Also in 1916, Lloyd George and the Control Board tried again to reduce the strength of whisky sold in munitions areas, this time to 28.6% ABV. The industry pushed back and eventually it was settled on that the strength of whisky everywhere in the UK, not just in munitions areas, was to be standardised at 42.9% ABV.

Then, in 1917 (with Lloyd George having formed a government as Prime Minister the previous December) it was decided that in munitions areas, whisky was to be bottled at no less than 28.6% ABV no more than 40% ABV. The rest of the UK were able to bottle whisky at the previously stated 42.9% ABV.

Most of these restrictions were lifted after the war, but 1920 saw duty once more. This time, manufacturers were banned from adding taxes to the price. It suddenly became impossible for most distillers to bottle anything above 40% ABV, somewhat standardising the strength.

Scotch Whisky Laws In The Modern Day

Post-World War I, distillers and manufacturers became accustomed to bottling whisky at 40% ABV, because it was the maximum strength that they could bottle at without paying huge amounts of duty.

In 1933, the first definition of Scotch in UK law was put forward, outlining the legal protection of Scotland’s national drink.

In 1988, the Scotch Whisky Act was passed, stating that whisky must be bottled at a minimum of 40% ABV.

This change in the law signalled a new era for Scotch whisky distilling, with distillers not bound by such a low and strict upper limit (the only limit now being that the spirit must be distilled at no more than 94.8% ABV).

Whilst there are some strict lScotch whisky laws, they are not nearly as strict as some of the laws surrounding other alcoholic beverages, such as brandy and champagne.

The laws are robust enough to protect the spirit, but lax enough that distillers have some room to experiment.

As of 2009, the official principal Scotch Whisky Regulations are as follows: :

- Scotch whisky must be distilled, matured, and bottled in Scotland.

- The whisky must be matured in an excise warehouse, or another “permitted place” (definition on page 3 of the SWR 2009)

- Scotch whisky must be aged in oak casks for at least 3 years.

- The only permitted ingredients are cereals (barley, wheat, rye, or grain), water, and yeast.

- The addition of “plain caramel colouring” (E150A) is permitted.

There are plenty of other stipulations for Scotch surrounding labelling, geographical regions, and more. You can read all of the up-to-date legislation in the Scotch Whisky Regulations 2009.

Political Gains or Quality Control?

The laws that govern the distillation, maturation, and bottling of Scotch whisky have a long and complicated history, beginning with distillers desperately evading the tax man, to a teetotal Prime Minister who wanted the UK to go cold turkey.

Despite the political history of Scotch whisky legislation, the laws do (sometimes by accident) ensure quality control.

For example, the law that Scotch whisky must be matured for at least three years began as a compromise between Lloyd George and distillers. The law was only meant to reduce the availability of the spirit in the short-term. However, that law now ensures that all whisky interacts with it’s cask for at least three years, imparting complexity and flavour onto the whisky. As such, a piece of legislation that was born of a political spat became one of the most important quality control measures in the production of Scotch whisky.

The same can be said for the 40% ABV law. It was not until the legal ABV of whisky was lowered that people really understood what lowering the ABV does to the quality of the whisky. If the alcohol content is too low then this compromises the flavour of the whisky, erasing the top notes from the spirit, causing loss of depth of flavour and complexity. After all, there is a reason that cask strength bottlings are so popular.

The flavour of whisky that drops below 40% is compromised massively, so much so that whisky that drops below 40% is no longer considered whisky at all.

And so, despite the foundation of many of the Scotch whisky laws being rooted in politics the laws do a fine job of protecting Scotland’s ‘water of life’. The spirit would not be as well protected as it is today without the political quarrels that eventually inspired change.

If you have any other fascinating facts or opinions on Scotch whisky legislation, we would love to hear from you. Get in touch via [email protected].