Brora distillery and Clynelish distillery are intrinsically linked and have been since their founding. These days the two distilleries are entities in their own right with Brora is set to reopen in 2021. However, it is safe to say that as well as being neighbours both distilleries are intertwined and bottles from both are highly sought after by collectors.

The Histories of Brora & Clynelish

You could say that both the Brora and Clynelish distilleries, that were built in 1819 by the Duke of Sutherland, were built on something of a tragedy.

When landowners in the early 19th century saw how much they could profit from sheep farming they forcibly removed tenant farmers from their land. The Duke of Sutherland was no exception to this, and subsequently established a number of businesses in Brora, including a distillery, which upon its founding, was named Clynelish distillery.

The distillery was not terribly popular in its infancy, but soon gained popularity when it changed ownership in 1896 when Ainslie & Heilbron, in partnership with John Risk, bought the distillery. By 1912, John Risk was the sole owner of the distillery.

Clynelish was absorbed by DCL (which would go on to become Diageo) in 1925. It closed during the 1930s and only produced a small amount of spirit during the war.

In 1968 to keep up with demands for blends, a new distillery with six stills was built across the road from the original Clynelish. This new distillery was initially also called Clynelish, and the stills in the new distillery were exact copies of the old one, so as to keep the distinguishing style that Clynelish drinkers had become accustomed to.

The two distilleries, Clynelish A and B, ran side by side for a year until in August 1968, the original distillery, was temporarily mothballed. In 1969 the distillery was resurrected as Clynelish B, and was later renamed Brora to distinguish the peated malt it was producing to meet the increased demand for peated whisky brought on by a shortage of peated Islay malt. Other than the shift to peated whisky production the stills at Brora are the same as those that are used at Clynelish, meaning that the two styles of whisky are linked through their production as well as by their shared history.

Brora and Clynelish are as close to siblings as you can get, with identical stills installed at each distillery. Clynelish and Brora do have their own distinct styles – Clynelish is often described as a waxy, new-make spirit, and Brora, peated and smooth. With Brora’s resurrection on the horizon, it seems very likely that these two distilleries will be active siblings once again.

The ‘modern’ Brora distillery

Brora distillery closed in 1983; a victim of the 1980s whisky loch and downturn in the market.

Since its closure, Brora has seen a drastic increase in value thanks to the scarcity of the stocks and the skyrocketing demand and appreciation for peated single malt whisky. It has developed a following of loyal fans, who were overjoyed at Diageo’s announcement that Brora is set to reopen. The reopening was delayed somewhat by the Covid-19 pandemic but the distillery looks set to start producing new spirit in early 2021.

The ‘new’ Clynelish Distillery

The ‘new’ Clynelish distillery is still in operation today. The spirit is popular and also provides 95% of the spirit for use in Johnnie Walker’s blends.

In 2018, Diageo announced plans to heavily invest in Scotch whisky tourism by building upgraded facilities at four cornerstone distilleries; Caol Ila, Cardhu, Glenkinchie, and Clynelish. As such you can expect big things from Clynelish in the coming years.

Future releases from Clynelish & Brora?

Work started on Clynelish’s renovation in 2019, and Brora looks set to have its grand reopening early 2021. But what of the whisky? Do the distilleries have any plans to release something new?

In 2020, a Clynelish 36-year-old was announced as the Whisky Show Old & Rare Bottling 2020. This triumph by Clynelish was intended to show how the waxy spirit stands up to the test of time and improves with maturation. The extremely limited bottling – only 128 were ever produced – was available for £995. Now, these bottles selling for more than £1,500 at auction.

Meanwhile, the teams in charge of resurrecting Brora have been working hard to make sure that every element of whisky-making at the new Brora pays homage to the old distillery. Meticulous research has taken place, including scouring archives and interviewing former employees to make sure that the distillery is set up exactly as it was before its closure in 1983. This will put the whisky makers in good stead to release some quintessentially Brora whisky in a few years time.

A 40 year old Brora was released in 2019 to mark the 200th anniversary, and these bottles now command around £3,000 at auction. We also wouldn’t be surprised if Brora release another super aged, limited edition whisky from their cellars to mark the grand reopening, so keep an eye out for these bottles as they are sure to be popular with collectors.

How Do Brora & Clynelish Compare?

Brora has become something of a cult classic among whisky lovers since its closure in 1983. As a result, Brora bottlings are always highly sought-after at auction.

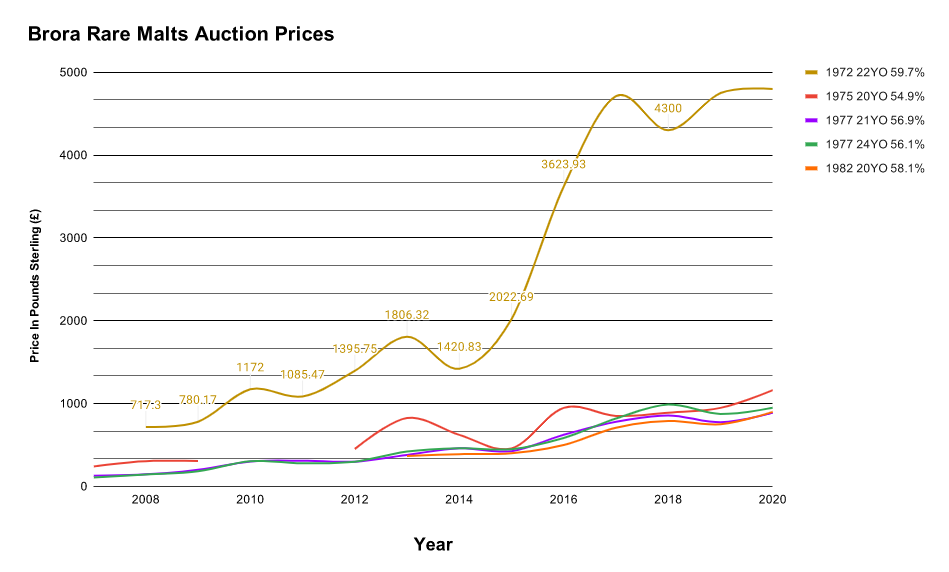

Below is a graph that shows the performance of Brora Rare Malts at auction since 2007.

As you can see, Brora Rare Malts have seen steady growth since 2007, with bottles that fetched £200 in 2007 now fetching upwards of £1,000. However, one malt, in particular, has seen massive growth, and that is Brora Rare Malt 1972 22-year-old. In 2008 the median hammer price for this bottling was £717.3. In 2020, the median hammer price was £4,800.

So, what sets the 1972 22-year-old apart from the others? The 1972 is the oldest vintage statement in the Brora Rare Malts series. As Brora was not opened until 1969, the 1972 whisky is some of the first spirit ever to be distilled at Brora. In fact, the oldest bottle of Brora whisky ever produced was distilled in 1972, and sold at Bonhams Hong Kong in 2017 for $18.9k. Therefore, whisky collectors may see the 1972 Rare Malt as an opportunity to own Brora whisky that was distilled in the same year as the oldest bottle of Brora whisky ever to be sold.

The other malts in the series have also seen impressive growth. As previously mentioned, Brora’s closure in 1983 meant that production was ceased, automatically making any remaining Brora stock more valuable as multiple collectors sought the same bottling. The increasing value of Brora Rare Malts is a testament to the power of public perception of a brand and how this can impact the status of a distillery.

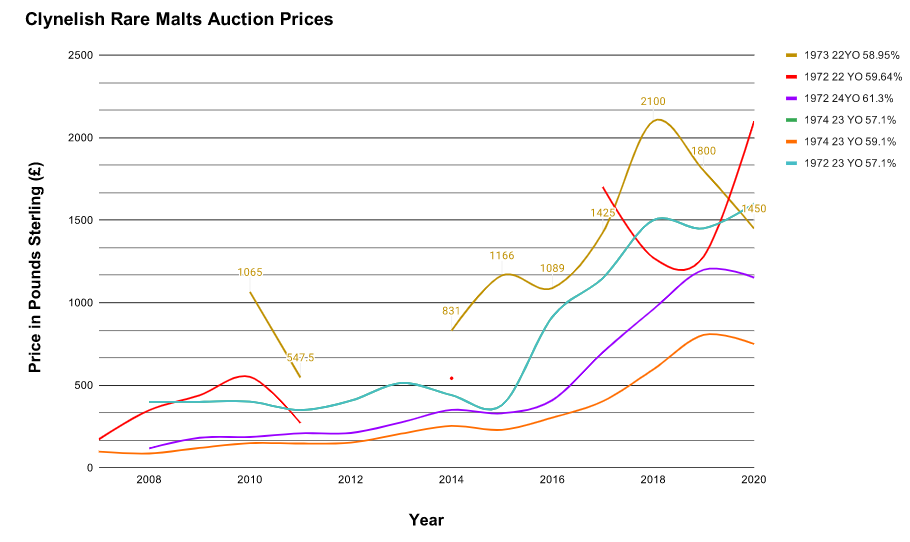

Clynelish Rare Malts, by comparison, have seen much more drastic fluctuations in value. For example, the 1973 22-year-old had a median hammer price of £1,065 in 2010, but this had nearly halved by 2011, to £547.50. This happened again between 2018 and 2020, with the median hammer price dropping from £2,100 to £1,450.

This drop in value could be due to a number of factors. If there are multiple of the same bottling up for auction then the competition to win the bottle is less fierce; why enter a bidding war when one will be sold again tomorrow? Value also depends on the condition of the bottles that are on sale, i.e. the level in the neck, the condition of the label, the condition of the capsule, the inclusion or absence of a box, the condition of said box. All of these factors contribute to how much a collector is willing to pay for a bottle. Therefore, auction prices are a good indication of the value of a bottle, but you should remember to consider the factors listed above when thinking about why a bottle sold for the hammer price that it did.

So, which is better? Brora or Clynelish?

The graphs above by no means suggest that Brora is a better whisky than Clynelish, but rather suggests that in collectors’ opinions, Brora is more sought-after.

There could be several reasons for this, not least being that since Brora’s closure, Brora whisky itself is by its nature limited as no stock has been produced since 1983. Diageo have also spent the last few years releasing limited edition high age statement special releases, which helps to build a brand’s perceived value with collectors.

Clynelish, on the other hand, has continued to produce spirit through to today. If you look at their more recent releases the age statements are much lower than those from Brora while it might be argued that Clynelish’s branding is pitched toward the more middle level of the whisky market – as shown with the inclusion in the Johnnie Walker experience. As such, while Clynelish bottlings can achieve as high a price as £11,000 this is only when the bottling on offer is extremely old and rare – usually from the old Clynelish distillery!

The two distilleries are a great example of how branding and a distillery’s position in the public eye affect the price of whisky bottles.

A brand is only luxurious as far as the public say it is luxurious. Brora and Clynelish are no different. However, it will be interesting to see what impact the substantial investments into both Clynelish and Brora will have on the whiskys’ demand, with Clynelish perhaps being a good one to speculate on in the coming years.